IWW: The Basics of Organizing (pamphlet)

|

No Personal Problems

The employer tries to make us believe that our problems are merely personal. For example: the boss calls Barbara into the office and writes her up for being late. Barbara explains that she was lat because her sitter was late. The boss says he's sorry, but he can't bend the rules for one person. As she leaves the office, Barbara may think: "But it isn't one person, it's everyone in the office. Everybody in this place has been absent or late at least once because of a problem with child care."

And it isn't just that office. Columnist Anna Quindlen wrote in the New York Times, "[What if a union of working mothers held] a one-day nationwide strike. In unison at a predetermined time, we will rise and say: 'My kid is sick, and so is my sitter' and walk out. Look around your office. Think how much work wouldn't get done."

The need for child care -- to chose just one example -- affects tens of millions of workers. The same applies to other "personal" problems such as reactions to chemicals, injuries, and stress. It is in management's interest to make ther problems appear to be "personal" so that management will not bear respnsibility.

Ask Questions and Listen to the Answers

You have a problem; where do you begin?

Some people when they first feel that they have been treated unfairly fly into a rage or start loudly crusading against the boss. This can be dangerous. Management jealously guards its authority in the workplace, and when you begin to question authority, you become a threat. In most workplaces, from the moment you begin to question authority, you become a troublemaker in management's eyes. If you have never before made any waves where you work, you may be shocked, hurt or angered by how quickly management turns against you. This is one more reason not to act aloneand also be discrete when you begin to talk to others.

Talk to your co-workers and ask them what they think about what's happening at work lately. What do they think about the problems you're concerned about. Listen to what others have to say. Get their views and opinions. Most people think of an organizer as an agitator and rabble-rouser (and there are times when an organizer must be those things), but a good organizer is first of all one who asks good questions and listens to well to others. Having listened well, the organizer is able to express not only his own views and feelings but those of the group.

Almost inevitably there will be some people who are more concerned than others, and a few of those people will want to do something about it. Those few people now form the initial core of your "organization." You might ask the two most interested people to have coffee or lunch with you, introduce them to each other, and then ask, "What do you think we should do about this?" If they are indeed ready to do something -- not just complain -- you are almost ready to begin organizing.

Map Your Workplace

Knowledge is power. Or at least it is the begining of power. You will want to know everything you can about your workplace and your employer. This will be a long-term on-going process of education. You should begin with your department. Remember, all the information you gather can be used by you against your employer or by them against you so, be sure not to let it fall inot the hands of management or their supporters.

The steward and/or shop floor activist cannot afford to overlook the natural organization that exists in most workplaces. Resist the tendency to complicate shop floor organization by establishing artificial structures or involved committees and caucuses without first taking advantage of the organization that already exists. "Mapping" your workplace will help you to communicate with your co-workers and increase the union's power.

Management has long understood the value of identifying informal workgroups, their natural organizers, and their weak links. In fact, one of the main thrusts of management training is to develop strategies to alter the psychology of the workplace.

United Parcel Service, for example, has developed its psychological manipulation techniques into fine art. The UPS manager's training manual, titled Charting Spheres of Influence, shows how to map the workplace to identify the informal work groups, isolate natural organizers or instigators in these groups, adn exploit the weak links, and in the end, break up the groups if they can't be used to management's advantage.

While most companies have not developed their techniques into the fine Orwellian art that UPS has, many do use some of the same methods. Have outspoken workers, instigators or organizers in your workplace been transferred, promoted into management or singled out for disipline? Are workgroups broken up and rearranged periodically? Has the layout of the workplace been arranged to make communication between workers difficult?

Do you get to walk around your job? Who does? Who doesn't? Are certain people picked on or disciplined by management in public? Do you feel you are always under serveillance? You get the point. All of the above can be used to break up unity and communication between workers in your shop.

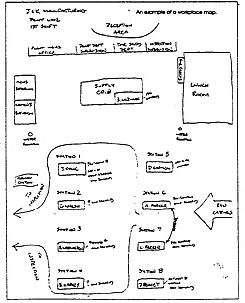

How to Map Your Workplace

If you work in a large shop, you may want to begin by mapping just your department or shift and then work with other stewards and/or shop floor activists to piece together a map of the entire workplace.

You can begin by drawing an outline of your department and putting in workstations, desks, machines, etc. -- a floor plan. Now, place a circle where each worker is usually stationed, and write in their names. If you can, chart the flow of production by using a broken line or arrow. Indicate on your map where members of management are usually stationed and their normal path through the shop. Mark places where workers tend to congregate (break areas, lunch rooms, bathrooms, water fountains).

Now identify and circle the informal work groups. Informal workgroups are groups of workers who work face-to-face with each other every day, They have an opportunity to communicate with each other every day while working and perhaps spend time together on breaks, eat lunch together, or generally hang out together.

Mark the influential people or informal workgroup organizers or instigators. In each group is ther a person who seems to enjoy a special influence or respect? Sometimes they are stewards or activists, but in many cases the organizers or instigators will not be. Do conversations in the group ever get into shop talk? If so, what do they talk about? Is there an unspoken code of behavior in these groups towards management or problems at work? Is there an informal production standard which is followed and enforced by group members?

If you are aware of loners or people who don't mix with any group, indicate that by using some special mark. Also, identify the weakest links: the company brown nose, perhaps a part-timer or new hire, and anyone who is particularly timid.

You may want to begin taking notes on each worker and record things as when the person started work, grievances filed, wether they have been active in any union projects, etc. Keep notes on seperate index cards in a file. [ed. or use your computer if you have one]

Your map may show you how the workplace is set up to keep people apart, a good enough reason for map-making. But the real reason for map-making is to develop more unity in the workplace.

Using Your Map

Let's say you have an important message to communicate, but you don't have the time or resources to reach every one of your co-workers. If you can reach the natural organizers in the informal workgroups and get them on your side, you can bet that the word will get around to everyone. Once organizers have been identified and agree to cooperate, it is possible to develop a network which includes both stewards and these de facto stewards who can exert considerable power and influence.

Informal workgroups also have the advantage of creating certain loyalties among their members. You can draw on this loyalty to figure out unified strategies for problems, and take advantage of people's natural tendency to stick up for those who are close to them.Sometimes it is necessary to negotiate between the workgroups which, while experiencing common problems, also have concerns involving only their own members. For example, at one shop, two informal wokgroups existed in the department. One group consisted of machine operators who die-casted transmission cases, and the other groupconsisted of inspectors. Management didn't allow inspectors to talk to amchine operators.

At one point management increased machine operators' production quotas, which caused inspectors to mark many of the pieces as scrap, because they were having trouble keeping up with production too. Both workgroups were facing pressures from the speed-up and tended to blame each other.

Eventually, representatives of the two workgroups out an arrangement to deal with the speed-up. It was agreed that the inspectors would mark as scrap any transmission case with the tiniest little flaw, causing the scrap pile to pile up. Management would then have to come up and turn off the machines in order to figure out what was causing the problem. Soon, each machine was experiencing a few hours of downtime every day. After a week of this, mamagement reduced the production quota.

Besides working with the group organizers, it is important to draw in the loners too. More than likely, their apathy, isolation, or anti-union ideas stem from personal feelings of powerlessness and fear. If collective action can be pulled off successfully and a sense of security established through the group's action, fear and feelings of impotence can be reduced.

If you have got a particularly tough character in your shop who seriously threatens unity, don't be affraid to use the social pressures that workgroups can bring to bear to get that person back in line. This applies to supervisory personnel too, especially the supervisor who likes to think he is everyone's pal.

Workplace Map

The Balance of Power

The bottom line for this type of workplace organization is to tilt the balance of power in the workers' favor. It can win grievances, for example. If grievances remain individual problems or are kept in the hands of just the steward or union higher-ups, the natural organization and loyalty that exist among workgroups is lost. Chances are that he grievance is lost, too.

However, it the workgroups can be used to make a show of unity, the threat that production could be hampered can be enough to force management into a settlement. For example, back in the die-casting plant: a machine operator was fired on trumped-up charges. A representative of that workgroup informed key people in the skilled trades who had easy access to all workers in the plant to tell them something was going to happen at lunch time in the lunch room.

At each lunch break, a meeting was held to explain the situation. It was decided to organize for a symbolic action. The next day black arm bands were handed out in the parking lot to everyone entering work. The key people in every workgroup were informed to use their influence to make sure everybody participated in the action. It was suggested that everyone had as off day once in a while, and it would be a shame if everybody had an of day at the same time.

After two days of this, the machine operator was brought back to work. Such an action would have been impossible without a recognition of the informal workgroups and thier representatives. The grievance procedure worked because management understood that the grievance had become the concern of all the groups and that problems lay ahead unless it was resolved.

Some Basic Principles

The following is a list of what successful organizers say are the most important principles to remember:

Your Legal Right to Organize

A. General

B. Your Right to Distribute Literature

C. Strikes, Pickets, and Other Protected Activities

Unless there is in effect a contract with a no-strike clause, you may engage in group action to force the company to accept union conditions.

Such activities are only protected under Federal labor law if done by two or more individuals together. Striking, picketing, petitioning, grieving, and giving group complaints to the U.S. Department of Labor are classic examples.

The right is protected by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which must receive and serve your charge within six months. However, the NLRB has a policy of defering action on such cases if there is a grievance procedure in effect which theoretically could resolve the issue.

CONTACT THE IWW GENERAL HEADQUARTERS AT

103 W. Michigan Ave.

Ypsilanti, MI.

48197 USA

Phone: (313) 483-3548

Fax: (313) 483-4050

E-mail: iww@igc.apc.org

LOCAL CONTACT